China’s economic growth slowed to 6.2% in the second quarter (2Q19) of this year, its weakest pace in at least two decades due to increasing trade tensions with the US. The slowing growth has also put pressure on domestic corporates with loan payments due.

Based on a report by Shanghai DZH Ltd, a financial information provider in China, defaults on corporate bonds in 2Q19 amounted to slightly over 60 billion yuan, almost comparable to that of the previous corresponding period. Last year was also the year when China recorded a new high in its corporate bond default at 128 billion yuan.

However, investors shouldn’t feel over-worried about China’s economic growth and corporate bond market default. China’s economy is expected to grow above 6% at the end of the year, a rate that is still higher than in many countries around the world, says Eric Liu, portfolio manager of the Asia Credit Team at BlackRock in Singapore. He adds that the country’s corporate default rate, while high, remains lower than the global average.

He says tariffs imposed by the US on China would potentially drag the latter’s GDP by 1% to 1.2% and economic activities in China have already faltered on the back of escalating trade tension. However, government policies will continue to support its economic growth.

“We believe a policy stimulus implemented by the Chinese government is likely to ofset any trade shocks. This includes an aggressive fiscal stimulus (including income tax and value-added tax cut and an increase in fiscal spending), easing monetary policies and continued interest rate reforms,” he says.

He adds that China’s GDP is expected to slow in the second half of the year (2H19), but it should fall between 6% and 6.5% as the Chinese government is also working to address structural bottlenecks through reforms. These reforms include the further opening up of China’s financial markets to attract foreign capital inflows that would transform the economy into a consumption based one that is more resilent.

Liu also points out that China’s onshore market high-yield bond default rate was 1.6% last year as compared to the global average of 2.5%. As at Sept 23, the rate was 0.8% year to date.

China’s onshore corporate bond default rate is expected to catch up with that of the global average slowly and normalise subsequently. But it is unlikely that investors would see a spike in the default rate, adds Liu.

“We believe the number of defaults will likely go up from a very low base, given ample liquidity in the market. We will likely continue to see corporate defaults as part of the normal business cycle but the possibility of systemic credit risk with a large number of defaults happening remains low,” he says.

Despite the higher level of defaults, Liu says investment opportunities have emerged within the domestic bond market.

He adds that the easing of fiscal and monetary policies by the Chinese government would support its economic growth and benefit bond issuers in general. On top of that, the Chinese yuan that is staying at an “appropriate level” at the moment could strenghten further, he adds.

“We expect the Chinese yuan internationalisation to play an essential part in China’s medium-term economic plan. The trade tension has accelerated such a move by the Chinese government.

“While this may cause an upside risk to the strength of the yuan against the US dollar in the near term (meaning that the yuan could appreciate more than the markets have expected), it is unlikely the Chinese government will let the yuan weaken significantly,” he says.

Based on findings by ICBC International Holdings Ltd, which is the Hong Kong investment banking arm of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, overseas institutional and individual holdings of yuan-denominated financial assets totalled US$717 billion as of 2Q19. Within that total, the share of yuan-denominated stocks and bonds as a percentage of total assets held by global investors increased to about 2.5% and 3% respectively.

Liu says further liberalisation of China financial markets would attract more foreign capital to flow into the country and benefit the country’s bond market.

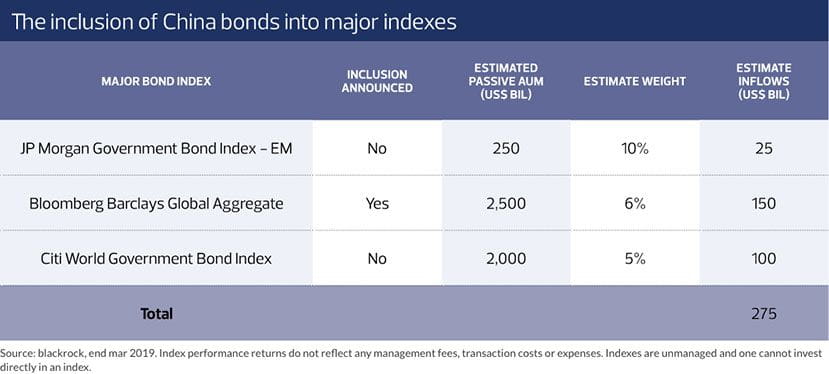

“The recent inclusion of the Chinese government and its policy banks’ bonds into the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index, as well as the inclusion of Chinese government bonds into the emerging market and global suites of JP Morgan local currency indices clearly reflect China’s determination to become a mature financial market that facilitates capital inflows,” he says.

Liu further explains that China’s bond market could be broken down into two categories, which are the onshore renminbi credit market and offshore US dollar Chinese credit market. Investors with the right strategy could generate extra returns by investing in both markets.

“There’s a very low correlation between the onshore and offshore assets, which allow investors to generate alpha through asset allocation.

”The significantly different investor base in both markets also create opportunities in price discovery between the onshore and offshore securities of the same issuers,” he says.

Liu says investors can also diversify investment risk by investing in both China onshore and offshore bonds. “Chinese US dollar credits is, in part, sensitive to the US Treasuries. Investing in onshore renminbi credit could help investors to diversify risk.”

On the onshore renminbi credit market, Liu favours government bonds given the government’s accommodative policy stance. “We are positive on state-owned enterprises given the higher all-in yield compared to offshore markets credits after currency hedging. In the high-yield bond space, we see value in the industrial sector for its quality carry and diversification as compared to the offshore US dollar Chinese credit market that has a smaller universe in the same sector,” he says.

After all, China has the world’s second-largest bond market that investors should not overlook, says Liu. As at January, the size of its bond market was US$12.4 trillion, according to BNP Paribas, a French international banking group. This was followed by Japan (US$12.1 trillion), Germany (US$4.8 trillion) and France (US$4 trillion). The US had the world’s largest bond market at US$26.3 trillion.

The key risks to China’s bond market are the prolonged US-China trade tension and an increase in default rates, says Liu. However, the Chinese government still has policy tools to manoeuvre such a challenging enviroment.

“It would issue more local government bonds in the near term to support infrastructure spending. This would be combined with further lending rate cuts under its loan prime rate reform and through open market operations. These actions would inject liquidity into the country’s economy and reduce refinancing cost,” he says.

As investing in China’s bond market could be a challenging task to individual investors, for those who are interested in seeking extra returns from the market could invest in RHB China Bond Fund, a fund that feeds into the BlackRock Global Funds-China Bond Fund (the target fund).

The target fund invests mainly in renminbi-denominated fixed income and non-renminbi denominated securities issued by entities whose core businesses are in China. It is also allowed to invest in the full spectrum of available fixed income transferable securities which include non-investment grade bonds in both onshore and offshore China bond markets.

The feeder fund aims to maximise total returns by investing at least 95% of the net asset value in the target fund. As of May 31, the fund had an assets under management for RM49.29 billion (US$11.9 billion) and it aims to raise RM100 million by the end of this year.